What Is Khadi?

Khadi refers to hand-spun and handwoven cloth. The raw materials may be cotton, silk or wool, which are spun into threads on a `charkha’ - a traditional spinning implement. The yarn is then woven into fabric using handlooms.

Khadi and the Swadeshi Movement

Khadi – the word conjures up images of Mahatma Gandhi and the Swadeshi (self-sufficiency) movement he led. Ghandi recognised the political importance of hand spun cotton (khadi)), and made it a cornerstone of his independence movement.

Ghandi spinning cotton in Ahmedabad c.1931

A humble fabric, hand-woven from hand-spun yarn, khadi was elevated into a symbol of defiance and freedom by Gandhi. For him, khadi embodied moral, social, economic and political values.

Gandhi began promoting the spinning of khadi for rural self-employment and self-reliance (instead of mill manufactured) in the 1920s, thus making khadi an integral part and an icon of the Swadeshi movement. Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule. The nation was encouraged to wear Indian fabric, an ideology which fuelled the nationalist movement.

The resumption of hand-spinning and other village industries was a way of restoring meaningful labour to the masses, of achieving economic independence and ultimately self-rule. Ghandi called for the the Indian people to take up spinning yarn, and weaving and wearing khadi. He disseminated his message by spinning in public while addressing gatherings, and simplified his dress so that he could identify with the masses and they could identify with him. Gandhi adopted the short dhoti woven with hand-spun yarn as a mark of identification with India's rural poor

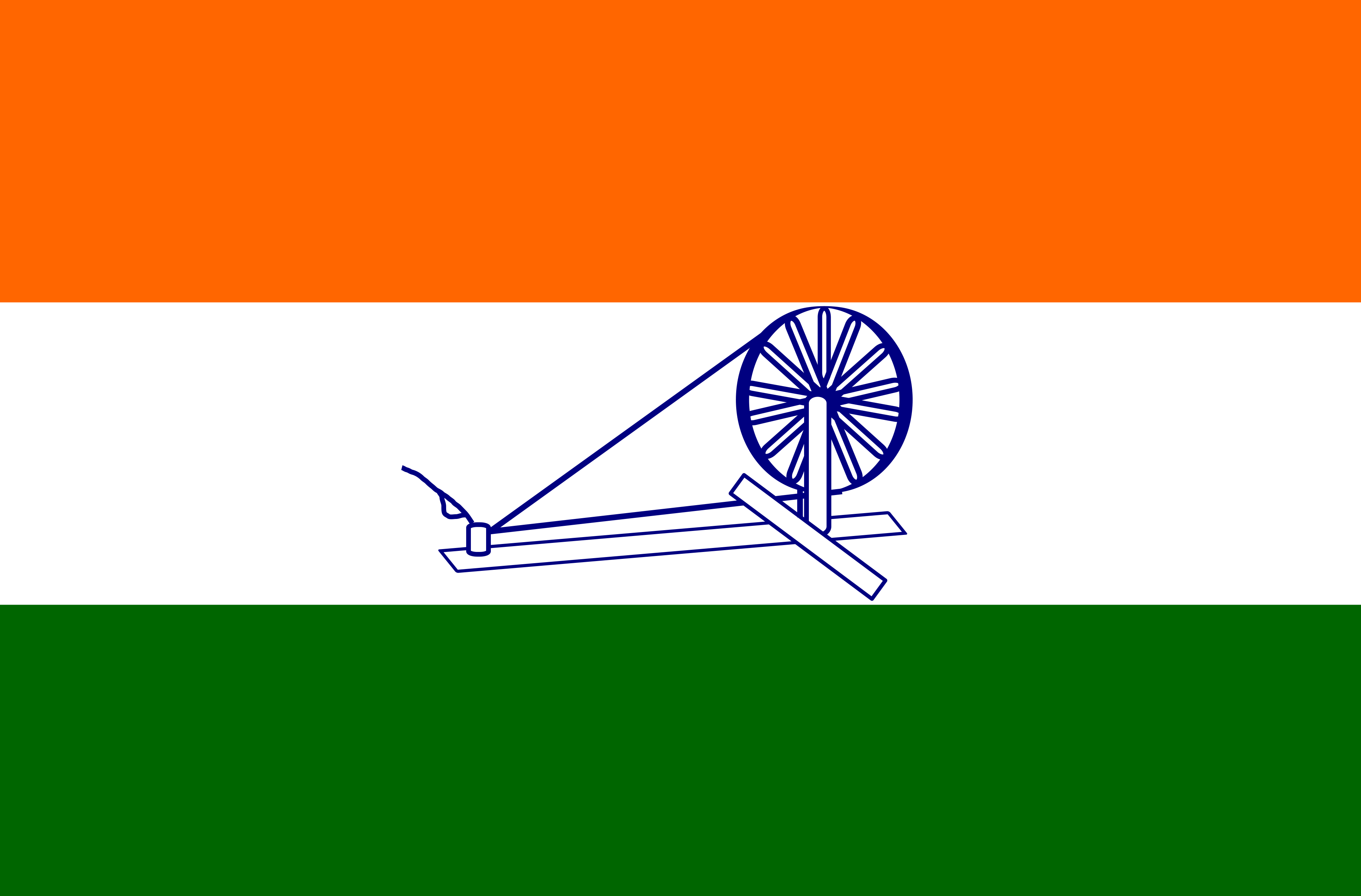

The Spinning Wheel or Charkri, as the Symbol of the Indian Flag

Members of the Indian National Congress (INC), the main political party opposing British rule, began wearing khadi from 1921 as part of their official programme of resistance. Recognising khadi as as central to their message of self-sufficiency, they incorporated the spinning wheel into the the design of a flag for the nationalist movement - firmly establishing khadi as as a symbol of the nation.

In 1947, the year of partition, the national flag of India replaced the spinning wheel at its centre with the Ashoka Chakra in navy blue - a wheel represented by the 24 spokes in Buddhism. By law, the flag is to be made of khadi.

The Nehru Jacket and the Ghandi Cap - the visual impact of clothing and cloth. The khadi cap Ghandi `designed’ became the iconic Ghandi cap. As the movement gained momentum the visual impact of his clothing and the large crowd of supporters wearing khadi and `Ghandi’ caps became powerful tools of protest.

Photo Left: Protesting the arrest of Ghandi, Bombay, 1930. Photo Right: Jawarhal Nehru, President of India’s Congress party. Photography by Margaret Bourke-White for LIFE Magazine, 1946

Jawaharlal Nehru, leader of the INC and later to become India’s first Prime Minister used the symbolism of khadi in many ways, including tailoring it into a semi-fitted coat with a closed collar, which became an iconic piece of clothing know as the ‘Nehru Jacket”

Khadi In Today’s World of Fast Fashion

Khadi has an enduring romantic association with artisanal knowledge and handmaking traditions that appeals to contemporary fashion designers, many of whom incorporate the fabric into their collections. INDIA in BALMAIN seeks to support such designers - currently stocking INJIRI, DVE and KARNAM.

Now is the time to recognise the beauty of khadi; deliciously soft, delicately textured and retaining the natural properties of cotton normally damaged during the machine-spring process. It’s a pleasure next to the skin and dances and floats with movement. Each metre of cloth represents hours of efforts by farmers, spinners weavers and dyers.

“The hand-loom weaver still exists amongst us, nor is it likely that he will ever cease to do so. Less likely still is it that machinery will ever be able to drive him from the field in India. The very fine and the rich decorated fabrics of that country will probably always require the delicate manipulation of human fingers for their production.” John Forbes Watson 1867

References

The Fabric of India V & A Publishing edited by Rosemary Crill